Lindsay Todd kindly decides to donate his R/C Spitfire to a museum run by the Wartime Aircraft Recovery Group

words & photos >> Lindsay Todd

What do you do when you get a bit emotionally or sentimentally attached to a model aircraft? It does happen; I’ve seen it many times and had it has happened to me on more than one occasion when, for no particular reason, a certain model becomes a favourite and even when it is looking well past its best, we just can’t let it go.

Enjoy more RCM&E Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

To a degree I enjoy this type of scenario as it means we have formed a relationship and it has become a good friend, reliable and trustworthy, and, after many hours of flying, full of memories. For those of us that commit to long hours in the workshop toiling over bits of balsa and ply this relationship is well established long before the model sees the light of day and we even think about flying it.

Many modellers have had completed models for years before committing them to a flight as the model is simply nice to have around and they enjoy the satisfaction of ownership of something that has taken time and effort to produce and which is now finished and ready to be cherished and taken care of.

Projects such as these can, alas, become hangar queens, gathering dust, taking up space and, worst of all, picking up casual damage over the years.

THE KING RUFUS

Some years ago, I took on a project to build a replica of my uncle’s Spitfire VB that he had flown with 92 East India Squadron, based at Biggin Hill in 1941. He was one of the many pilots that were sadly killed in action. However, with the family connection, it would obviously be a nice tribute to build and fly an R/C replica. The model was built using the DB Models Spitfire kit and I undertook some quite extensive research into the life and history of both my uncle and the aircraft he flew both before and during the project.

The particular aircraft was a Spitfire VB, W3331, ‘The King Rufus’, which had been what was known as a presentation aircraft, a term that was utilised for an aircraft that had been funded by local communities and organisations. In total the project took about a year to complete and it was both absorbing and enjoyable on many levels, not least digging up some family history and having the family connection to the model I was building.

In practice I flew the model three or four times and then, scared of damaging her, being mindful of the emotional ties, I acquired a Kyosho Spitfire 90, which I repainted in the same colours and markings. I flew that instead, retiring the main project to the workshop.

After five years of gathering dust and a house move, W3331 was in need of some TLC. The DB Spitfire is not a small model at 81-inch wingspan and takes up a fair bit of space, despite being neatly stored. It was time to do something positive with her and the opportunity almost came about by complete chance.

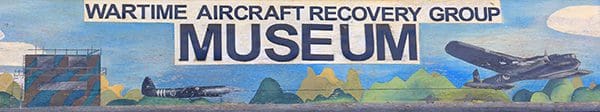

WARTIME AIRCRAFT RECOVERY GROUP

My wife and I had been down to Shropshire and with the afternoon mostly free, we found ourselves in the location of Sleap Airfield. I have had the pleasure of flying with the Sleap Model Flying Club in the past and a previous work colleague used to fly full size gliders there. Being an operational airfield there is always something to see, plus there’s the bonus of a good café, which can make for a fun few hours simply watching aircraft. I had also forgotten about the rather good museum that operates on the site, which is run by volunteers and is called the Wartime Aircraft Recovery Group.

As the name suggests the museum consists largely of parts from wartime aircraft that have been recovered and donated, largely from the Shropshire area, and given Sleap’s locality the diversity is quite extraordinary. I was particularly pleased to see a section devoted to the Horsa Glider as I have a further family connection here with my father, who had flown the type until a major crash, which he survived, caused by the elevator or rudder cables jamming down the rear fuselage, I believe.

The museum boasts a number of aircraft engines, canopies, wing sections and undercarriage parts, and is just a really fascinating place to look around. In some ways the small scale of the operation is to its benefit as although the exhibits may be less pristine, they are clearly used and have history associated with them, which is immediately apparent. They are not shiny and polished like something straight out of a factory showroom. I like the authenticity that you get from the real enthusiasts that run the museum, who like a bit of muck, grease and oil.

Perhaps most impressive is the fact that this whole operation is run by volunteers who manage all aspects of the museum in a most impressive way. When I suggested I had a model that I was looking to donate they were delighted to be able to accommodate me and, together with the Horsa connection with my father, it seemed appropriate that our family’s association with aviation should all sit together.

Perhaps my own somewhat lesser connection as a model aircraft builder and designer has kept the family tradition surprisingly tightly knit after all, and it is now all under one roof. So, thank you Sleap Airfield and the Wartime Aircraft Recovery Group for making this possible.