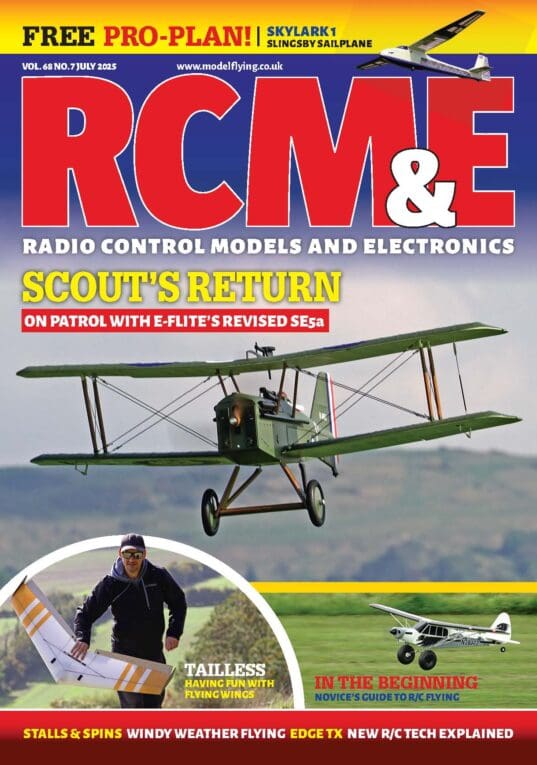

I’m pleased with the finish on my Verosonic

Litespan covering material has been available for many years now, used as a heat-shrink ‘tissue substitute’ on free flight and the more petite, traditionally-constructed R/C models. Whilst the oldfashioned tissue and dope covering application hassles are absent, Litespan nevertheless presents the first-time user with new set of equally-challenging problems, and it remains a material that can be rather tricky to master – especially if you use it infrequently.

A while back, I covered both a Grüner electric-powered R/C ‘Tiger Moth’ and a Veron ‘Verosonic’ F/F glider with Litespan and was quickly reminded of just how demanding the stuff can be to apply if you’re not fully tuned in! Based on that slightly anxiety-producing experience, I thought I’d pen this article to remind everybody of how best to deal with this revolutionary but challenging airframe-covering medium.

Enjoy more RCM&E Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

LITE YOU ARE

What exactly is Litespan? It’s doubtful that Solarfilm, the manufacturer, will give away its formulation secrets anytime soon, but in practical terms it’s a super-light, very strong, airtight and waterproof paper-like material that’s resistant to both glow and diesel fuels, and it accepts most paints safely without nasty reactions occurring. According to Solarfilm, Litespan’s high strength-to-weight ratio is the result of an ‘interwelded’ polyester fibre network, a characteristic that makes it much tougher than conventional tissue and dope over open structures.

Litespan has no factory-prepared adhesive backing. Instead, a specially-matched glue called Balsaloc must be applied to both the Litespan’s airframe-contact surfaces and the model’s timber structure before the material can be attached to the airframe. When the Balsaloc has dried, the material is ironed on in much the same way as plastic film, but overlapped edges must be treated with separate brushed-on beads of Balsaloc before ironing them down – more about that later.

Now, a very important point – ensure that your Balsaloc is fresh! Buy a new jar and dispose of any partially-used stuff you may have lying about that’s more than one-year old. Why do I say this? Because, the one-and-a-half-year-old Balsaloc I ‘pressed’ into service on the aforementioned models wouldn’t work properly, and the Litespan didn’t stick down with the bond strength that it should normally achieve.

Get a fresh jar of Balsaloc!

Get a fresh jar of Balsaloc!

Litespan comes in nine colours, described as ‘Tissue Grain’ and ‘Scale’. With the exception of silver, the material can be applied ‘glossy’ or ‘dull’ side out. Silver must always be applied ‘silvery side’ out. In their unpainted state the Tissue Grain colours weigh less than one-ounce to the square-yard while the Scale colours weigh exactly one-ounce to the square-yard. The Tissue Grain colours are: yellow, orange, red and blue; Scale colours are: white, black, silver, WW1 dark green and antique cream. Not exactly a gargantuan range there, it has to be said, but some snazzy colour schemes can be easily executed with a little practice and imagination. I sometimes purchase the entire Litespan colour range just to toy with different colour scheme combinations!

A LITE TOUCH

Very few application tools are required with Litespan. A sharp single-edge razor blade, some new keen number 11 scalpel blades and scissors easily cut the material to shape. A ‘normal’ or chisel-tip modeller’s iron is used almost exclusively for sealing and shrinking, though a ‘turned-down’ heat gun may also be employed for shrinking large areas – providing the Litespan doesn’t overheat. The Litespan application ‘tool kit’ is completed by a several cut-up chunks of soft cushion foam which are used as applicators when coating the airframe and covering with Balsaloc.

SHINING LITE

In common with all iron-on coverings, the underlying airframe must be as blemish-free as possible before applying the Litespan to obtain the best possible surface finish. The thin-gauge covering skin is only as good as that what lies beneath, so do strive to get that airframe structure really smooth.

First carve any oversize balsa sheet or blocks, such as wing-/tail-tips, glider nose-blocks and cowl cheeks, down almost to the finished shapes with a razor plane fitted with a sharp new blade adjusted for the best timber-carving depth. Stop when the sheet/block profiles are almost correct so that glass-paper and a sanding block can finish the job. It may be necessary to initially mark centrelines in Biro on wing-/tail-tips and glider nose-blocks to get a truly symmetrical carving result.

The airframe is sanded all over when the sheet/block portions have been carved down to the ‘roughly streamlined’ stage. Start with 180-grit glass-paper and work down (up?) to 400-grit. I often go as fine as 800-1000-grit, but that’s not really necessary, unless you’re an obsessive-compulsive aeromodeller like wot I am!

Airframe preparation is essential, the Litespan finish will only be as good as the surface underneath

Airframe preparation is essential, the Litespan finish will only be as good as the surface underneath

Initially use the 180-grit glass-paper on a block to smooth out large areas such as the fuselage and the wing/tail expanses. Begin by grinding down the roughly-carved sheet/block areas to match the main fuselage/flying surface profiles and then completely unify each airframe component by working your way across the large areas using both a circulating and 90-degree forward/back/left/right pattern. Take care not to crack fragile stripwood fuselage stringers or weak wing/tail ribs on the more vulnerable open framework structures. If breakages do occur, knit the crumpled structural member back together to re-establish correct alignment, squirt some thin cyano over the evened-up crack, and re-sand smooth when the glue has dried.

When the entire airframe is blended with the 180-grit glass-paper move on to the finer grits, but before doing so stuff any dents and dings with lightweight model filler. A small amount of water dribbled onto minor hollows also works effectively to re-swell the balsa back to its original ‘unbruised’ contour. When the dents/dings are treated, carefully sand back around each one locally with 400-grit, and then go over the entire airframe with the same paper. Take care at this point! Fine-grit glass-paper clogs easily with embedded filler and balsa dust, so check it regularly and brush/tap excess clogged filler/sanding dust out of the glass-paper surface at frequent intervals.

When the main airframe sanding is complete, I use 800-grit glass-paper freehand where open structure and sheet/block areas meet to get super-smooth ‘structural transition points’. A delicate touch is needed when doing this job so as not to score the timber. As just mentioned, smooth glass-paper can easily scratch already-treated balsa if the grit gets clogged!

LITE HEAT

Before applying the Litespan ensure that the temperature of your modelling iron is set correctly. Different temperatures are used for tacking and shrinking the material, and it’s extremely important that the various temperature values are observed for a truly successful covering job. Excess heat is most definitely counter-productive and will cause the material to slacken off permanently!

I suggested earlier that a heat gun could be used for shrinkage of large areas. Try to avoid this route if posible, but if you do go that way ensure that the Litespan has been pre-tensioned as much as possible, turn the heat gun down to its low setting, and hold it over any given area only as long as it takes for wrinkles to dissipate. I say again – too much heat damages the Litespan fibres irrevocably!

Edge-tacking and sticking down over solid surfaces is conducted with the iron set between 90- and 100-degrees C. Shrinking is carried out at a temperature of between 125- and 140-degrees C. Establish these temperature ranges in advance with a Coverite thermometer and mark the settings on your iron’s dial. Remember to be careful when pressing silver Litespan down over sheeted areas. Excess heat and/or iron pressure can easily mar the finish.

LITE ON

Typically, each wing half is covered in two Litespan panels – bottom and top. The horizontal tail takes four panels – bottom and top each side. The fin uses two panels – left and right. When wrapping up the fin on power models, position the Litespan panels so that the covering on the exhaust emission side overlaps on the opposite side of the fin. This usually means covering the left side of the fin first, but of course that arrangement is reversed with inverted engines. Control surfaces use two panels each – bottom/top on ailerons and elevator, left/right on the rudder (bearing in mind the previous comment about exhaust emissions).

The fuselage is covered to suit the various contour breaks in the following sequence: bottom front/rear, sides left/right and front/rear top decks. The nose-block on gliders and wing-/tail-tips on all models may be covered separately if appropriate, for example if they feature pronounced compound-curvature or if the colour scheme incorporates contrasting trim at these points.

Litespan is applied using slightly differing techniques for open and solid surfaces. Let’s begin with a typical open framework.

LITE WORK

Remove the clear backing and place the full Litespan sheet on a large cutting mat or piece of hardboard with either the glossy or dull side up, depending on the external surface finish you require (with the exception of silver, as mentioned earlier). Before cutting out the airframe-shaped pieces, tape the Litespan taut at each corner and mid-way along its width and breadth.

Use the airframe components as cutting patterns by placing ’em directly down on the sheet one at a time and trimming around each item 1” oversize (and 2”–3” oversize where compound-curves occur) with the super-sharp number 11 scalpel blade. As the airframe component covering pieces are cut out, the Litespan sheet will become unstable, so either re-tape locally or simply press the airframe component down firmly by hand while you cut around it to prevent slippage.

Use the airframe components as cutting patterns by placing ’em directly down on the sheet one at a time and trimming around each item 1” oversize (and 2”–3” oversize where compound-curves occur) with the super-sharp number 11 scalpel blade. As the airframe component covering pieces are cut out, the Litespan sheet will become unstable, so either re-tape locally or simply press the airframe component down firmly by hand while you cut around it to prevent slippage.

Choose the airframe component you wish to cover first. With a wing panel, for example, apply the Balsaloc sparingly with the foam pad applicator over the entire wooden structure and the contact surface of the cut-out Litespan covering panels. It’s recommended that you tape down the individual cut-out Litespan pieces while you sponge on the Balsaloc, but I haven’t always observed this recommendation and no real problems occurred, providing that each piece was securely hand-held.

The main snag with applying Balsaloc to an unanchored covering panel is that it can move and become contaminated by residual Balsaloc on its external surface. Solarfilm also recommend that you don’t apply Balsaloc all over on covering panels going onto open framework structures, presumably to save weight. Here again, I ignore the advice and just coat the entire panel. So far, the additional weight gain seems less than negligible!

The main snag with applying Balsaloc to an unanchored covering panel is that it can move and become contaminated by residual Balsaloc on its external surface. Solarfilm also recommend that you don’t apply Balsaloc all over on covering panels going onto open framework structures, presumably to save weight. Here again, I ignore the advice and just coat the entire panel. So far, the additional weight gain seems less than negligible!

Allow the Balsaloc to dry for fifteen-minutes until the adhesive goes from white to clear. Store the foam pad applicator inside the Balsaloc jar with the lid on to prevent it hardening up, or rinse the pad clean under the cold tap if you’ve finished all the Balsaloc-ing work in one go.

Tack the wing bottom panel in place using the tip of the iron, following the sequence shown in the Litespan instruction sheet. Ensure that the panel is completely wrinkle-free but not so tight that it distorts the structure. Having said that, I have found that stubborn wrinkles on undercambered wings for example do need extra localised heating and stretching as part of the main tacking/sealing sequence to get a really satisfying tight final shrinkage. If the wing structure does warp a little, it’s possible to straighten it out again when applying the opposing top surface covering panel.

My Protech mini tacking iron is a blessing in situations like this….

My Protech mini tacking iron is a blessing in situations like this….

With the initial tacking completed, fully seal around the lower wing panel edges, then trim off the surplus material so that a 1/4” overlap can be ironed down on the top surface. Brush on a bead of Balsaloc all around the top wing panel perimeter over the previously-sealed Litespan edges and 1/4” within the underside covering perimeter – this in preparation for attaching and sealing the top Litespan panel. Crank up the iron to the shrinking temperature. Start on the underside root area and slowly go over the entire surface towards the tip – it’s okay if the iron touches the Litespan here. The Litespan will tighten gradually, hopefully becoming totally smooth in the process. As you shrink the covering, check frequently to ensure that the wing panel isn’t warping downwards.

…..or this.

…..or this.

If it is, hold it gently but firmly against the warp as you continue to shrink the material. Keep the ‘biased’ grip on until the Litespan cools and, with luck, the warp will have lessened.

Remembering the required iron temperature adjustments, tack, edge-seal and shrink the top wing panel in the same manner. It will be possible to permanently cancel any stubborn warps when applying this opposing covering panel by localised heating and hand-held structural over-bending while the covering cools.

The remaining tail and fuselage airframe components are covered using the same ‘gluing’, sealing and shrinking techniques, bearing in mind the recommended panel-laying sequences quoted here earlier, and which are illustrated on the Litespan instruction sheet.

Compound-curved areas such as wing-/tail-tips, fuselage nose blocks, cowl cheeks and top decks may require covering with separate Litespan panels, though this isn’t always the case. Whether these potentially tricky airframe areas are covered in one or more pieces, the covering will most likely need scalpel-nicking into ‘fingers’ and mild ‘heat-moulding’ and hand-pulling to conform to the curves when ‘the heat is on’. That’s the reason why you need so much excess covering material around compound-curves – so that the covering can be heat-pulled past the required cutting-line to give a neat edge.

HARD LITE

An all-sheet airframe is covered using the same panelling sequence suggested for the open framework structure and the Litespan and airframe are also treated with Balsaloc in a similar manner too. It’s wise, however, to apply Balsaloc to either side of very thin sheet components to stop ’em warping even before the covering goes on! The actual method for applying the individual cut-out Litespan covering panels is a little different to the open structure concealment scenario though, and it goes like this…

Centre the first covering panel over the chosen component’s ‘first contact’ surface and, with the iron set at tacking temperature, iron it down directly from the mid-point outwards. Work slowly outwards in a ‘star’ pattern so that any trapped air is expelled as you press the material into contact with the wood.

The Litespan should bond smoothly in place as you go. If it wrinkles excessively as you ‘do the ironing’ reduce the temperature a little and/or heat-pull the wrinkle out. When the Litespan is stuck firmly to the entire intended contact area, trim off the excess and seal down a 1/4” overlap all around on the opposite side. The opposing side of the component is covered and edge-sealed in the same way, remembering to treat the overlaps with Balsaloc as previously described.

The Litespan should bond smoothly in place as you go. If it wrinkles excessively as you ‘do the ironing’ reduce the temperature a little and/or heat-pull the wrinkle out. When the Litespan is stuck firmly to the entire intended contact area, trim off the excess and seal down a 1/4” overlap all around on the opposite side. The opposing side of the component is covered and edge-sealed in the same way, remembering to treat the overlaps with Balsaloc as previously described.

Naturally, flat-sheet expanses and ‘single-bend’ curvatures are the easiest to do but, as with the open structures, compound-curve sheet/block areas are trickier to conceal. Treat these curvy bits as I’ve just described for the open frameworks.

TURNING A CORNER

I’ve already said this, but don’t forget that everywhere Litespan overlaps, a thin bead of brushed-on Balsaloc must be previously applied and allowed to dry. Use a pointy-tip 1/8” artist’s brush for this tedious task and wash it out under the cold tap, drying it off with kitchen towel when you’ve finished. It’s easy to forget about coating nooks and crannies such as open cockpit rims and firewall/radio bay bulkhead edges with Balsaloc, but if you omit such spaces then the Litespan will lift when the model’s being handled and flown. It’s also prudent to cover small tricky corners like the tail-to-fuselage junctions and wing fillets first prior to covering the main airframe portions. Doing all the hard-to-reach awkward corners at the outset will ultimately deliver a very neat finish.

LITE SHADES…

Various ‘graphic-designs’ cut from contrasting colours of Balsaloc-treated Litespan can be stuck down on top of the main covering with a cool iron. Assorted shapes such as cheat-lines, chequer-board squares and letters are readily ‘doable’ with a bit of practice. Litespan also takes either sprayed- or brushed-on Solarlac, Humbrol, Revell and cellulose paints, but be sure to check first for reactions on scrap material if using paints other than those listed. It must be mentioned that the smaller types of flying model that Litespan is designed for are better kept, well, as ‘light’ as possible, so I’d advise that any paint trim is kept to a minimum. Having said that, the Litespan-clad Grüner Tiggie was actually sprayed with silver dope as per the full-size with hand-painted registration letters added, and it still remained extremely light indeed.

HOT LITE

Finally, some more words about Litespan and temperature. If the Litespan wasn’t initially applied tight enough you may have insufficient shrinkage, and it’ll look dreadful! Only two irksome options exist here – live with it, or remove the offending covering by re-heating the edges and pulling it off and replace with a new, more taut, panel. I had to initially replace not one but two saggy wing covering panels on the Grüner Tiggie, and was rather peeved – to put it very mildly!

Even when properly applied and shrunk, Litespan can still slacken off slightly if exposed to severe temperature variations. Should this happen, it can be tightened up again with the iron at the shrink setting providing that it wasn’t overheated in the first place. Personally speaking, on the few models I’ve covered with Litespan, I’ve found that it stays pretty taut most of the time and only a slight touch of the hot iron is needed every now and then.

For the actual Litespan-application process, I highly recommend the use of both a modeller’s iron and a Protech mini tacking/sealing iron. The latter item is absolutely indispensable because it can get into tighter spaces than the modeller’s iron by virtue of its interchangeable flat and concave-curved tips. In fact, I often use this iron exclusively for both sealing and shrinking Litespan as it is particularly good for smoothing out stubborn wrinkles between wing rib bays and fuselage stringers at its hot setting using the ‘heat and pull’ method. I’ve had enquiries about where to get this item on many occasions in the past, and can now tell you that its Product Code is: TO166UK and the price in 2007 was £17.99. Contact Ripmax if you’re desperate to get one. They hopefully can advise interested parties of current availability.

DIMMING THE LITE…

That’s about it. I hope that this article has been of some help to you if/when you try covering a model with Litespan. If you have any further questions, feel free to get in touch at [email protected]